“Bonaventure to me is one of the most impressive assemblages of animal and plant creatures I ever met.

I was fresh from the Western prairies, the garden-like openings of Wisconsin, the beech and maple and oak

woods of Indiana and Kentucky, the dark mysterious Savannah cypress forests; but never since I was allowed

to walk the woods, have I found so impressive a company of trees as the tillandsia-draped oaks of Bonaventure.

I gazed awe-stricken as one new-arrived from another world. Bonaventure is called a graveyard, a town of the

dead, but the few graves are powerless in such a depth of life. The rippling of living waters, the song of birds,

the joyous confidence of flowers, the calm, undisturbable grandeur of the oaks, mark this place of graves as

one of the Lord’s most favored abodes of life and light.” – John Muir, “Camping Among the Tombs,” 1867

My introduction to Bonaventure Cemetery occurred over a decade ago. The year was 2006, and I was exploring the city I had recently moved to, without really understanding where I was going or what I was looking for. But I had heard of Bonaventure, and it was the mysterious scenery and remote location that drew me in. Despite barely tapping into the colorful history surrounding me, I became mesmerized, simply by taking a walk. This is not a bad way to go about it, but if you do a little reading beforehand, you will have an awakening. This is not just a cemetery. It is a flourishing forest, filled with the songs of birds, the peaceful calm of a sacred ground and the mysterious unknown of the heavens. It is a place where history, art, architecture, nature and the most intimate of stories merge together. Deep and painful scars exist within these grounds, but few places on earth could could be more healing. If you look closely, you might even catch a glimpse of Heaven. Bonaventure could easily be described as an enchantress, romancing her guests with quiet whispers and unexpected gifts in a delightful, secluded and solitary escape. Visit alone, and you will see things you wouldn’t otherwise see, hear things that cannot be spoken to you and learn things that cannot be taught. In the words of Oscar Wilde, “The secrets of art are best learned in secret, and that beauty, like wisdom, loves the lonely worshipper.” Interestingly, Oscar Wilde visited Bonaventure, himself, and he described the cemetery as “incomparable.” Indeed.

Bonaventure is a traditional Victorian Era Cemetery, or sculpture garden, and one of the most highly acclaimed in the world, located on a bluff with views of the Wilmington River and salt marsh. In just 160 acres, oak trees from the 1800s stand mighty and tall, breathtaking miles of azaleas blossom in the spring, moss-covered stonework and cast iron fences divide the landscape, impressive monuments and 25 historic mausoleums proudly declare Savannah names, and a dozen underground chapels and buried treasures secretly lie deep beneath our feet. Signatures of great artists have been carved into stone throughout, many of which are attributed to prominent sculptor, John Walz (1844-1922). Walz was born in Germany, studied art in Paris and was commissioned by the first Director of the Telfair Academy of Arts and Sciences in Savannah to carve Michelangelo, Rubens, Raphael, Rembrandt, and Phidias, which are still located at the Telfair Academy on Telfair Square. Walz did carvings for many prominent architectural buildings in Savannah, but over 100 of his works are located right here in Bonaventure. Another famous sculptor born in Italy, Antonio Aliffi, came to Savannah to work for Walz. In addition to carving many monuments around Savannah, he assisted with carving Mount Rushmore. Countless other architects and artisans’ work can be found here, and styles range from High Victorian Gothic to Classical Roman, Greek and Egyptian, making Bonaventure a rare kind of outdoor museum, which the public is lucky enough to have free access to.

Early on, tourists were drawn to Bonaventure, not only as a cemetery and place of remembrance but as a scenic and picturesque park where they could picnic and mail postcards from. Death was romanticized in the Victorian Age, and now we can experience that romance through the portal of Bonaventure. Suddenly, the name makes sense. Perhaps Bonaventure, meaning “buona ventura” or “good fortune,” helped define Bonaventure’s destiny? Or, maybe there was a purpose before it even had a name because we couldn’t be more fortunate today. The name just fits. It must have been a beautiful place when it was nothing more than untouched wilderness, and certainly, it was someone’s good fortune to have found it, but if only they knew what it would become. Many people have lost their lives inside this cemetery, and thousands more have been laid to rest here, but the miracle is what has transpired from such unimaginable heartache. An overabundance of love and hope is eminent inside this blazing fortress of life. Countless voices have left untold hopes, wishes, dreams and prayers all around. Their words are still present, and maybe a piece of their soul will forever be traced back here. For me, personally, Bonaventure is a safe haven, filled with memories. It is a place of music, midnight eclipses, rainy walks, sunsets on the river, glasses of champagne, birthday surprises, 4th of July celebrations, romance, reflection and joy. With each visit, memories reemerge from the past and mingle with the present, lingering in the footsteps left behind. The beauty of Bonaventure is you can share your life with things eternal and gain something back from that heavenly realm. Great mysteries and truths will always remain ever-present and protected here.

Why is it Bonaventure has remained so protected? Why is it so many people love walking among the headstones in this timeless hideaway? Something sustains all life around it, and I like to think the trees have something to do with it. Maybe the massive live oaks are reaching out towards the heavens to bring life back, or maybe they’re reaching out toward Heaven to transmit life from the earth and are somehow connecting the two worlds. Perhaps, even, every soul resting here has been assigned one of these guardian angels. Some cemeteries are replacing tombstones with trees (or cemeteries with forests) to provide an enduring, living memorial. It seems it was Bonaventure’s fate to offer such a living memorial alongside spectacular tombstones. Maybe the trees were planted hundreds of years ago, so that one day, they would memorialize our loved ones. They are nature’s own art, honoring those in Heaven the same way we sculpt and carve into stone. One hundred years from now — and another one hundred more — may others have the same good fortune of experiencing what may never be again.

Now consider the past. In the words of local tour guide, Shannon Scott, “In order to truly appreciate Savannah, you have to understand it’s not only a story of what’s here but also what’s left. It’s a war story of sorts.” The beginning of Bonaventure’s public cemetery dates back 173 years to 1846, but the history of the property dates back over 250 years to a privately-owned plantation and one of the first founded in Georgia. Englishman, John Mullryne, first settled on the 600-acre plantation around 1762, almost thirty years after the city of Savannah was founded, and he named it Bonaventure. It was this time many of the trees you see in Bonaventure Cemetery today were planted, long before the war, making them over 250 years old. They are now listed on the Georgia Landmark and Historic Tree Register. John Mullryne’s family and the Tattnall’s (related by marriage) owned the property during the American Revolutionary War, or the American War for Independence (1775–1783), but they were banished after the war for being British Loyalists. The property was purchased by the Habersham’s, friends of the Tattnall’s, then bought back by the Tattnall’s son in 1785. After being passed down twice within the Tattnall family, it was sold to Peter Wiltberger, owner of the Pulaski House hotel, who initiated the transformation into a public cemetery in 1846. Initially, the portion of land dedicated to the cemetery was known as The Cemetery at Bonaventure but later changed to Evergreen Cemetery at Bonaventure. In 1907, sixty-one years later, the City of Savannah bought the property and renamed it Bonaventure Cemetery, which concludes the ownership timeline.

Before the property became a cemetery, the plantation witnessed an impressive brick mansion being confiscated, sold at auction, burned in a fire, rebuilt, and burned again in the early 1800s, before turning into ruins and vanishing forever. Although possibly urban legend, the following excerpt has been written describing the fire:

“It was the occasion of a scene of dramatic effect. Fire broke out on the roof while a number of guests had assembled

with their host in the dining room to partake of a dinner. Do you picture a scene of consternation, of confused rush hither

and thither, to escape the doomed house? Not so. The stately host, stifling his personal feelings before the inevitable, with

the grace of a Chesterfield invited his guests to follow him to the garden, where the servants had preceded with the

dining-table. There, in the glow of the burning house, the dinner was eaten. Fancy the scene. The lurid sweep of the flames,

unchecked by an opposing element, their ferocity fed by increasing material until all within reach was reduced to ashes

or shapeless ruins, and there, within a stone’s-throw, around the bountiful table sat, the host with his subdued guests,

for it is not in human nature to suppose them all heroic, the host, with many a jest and sparkling word, diverting their

attention from the blazing fire, which engulfed his home. Verily, of such stuff are heroes made, and so proved the Tattnalls.”

– Historic and Picturesque Savannah, by Adelaide Wilson

A wedding and two births occurred at Bonaventure when the first family lived there, and one of the children, Josiah Tattnall Jr., would become the first native-born Georgian governor. In these early years, it was a place of joy, celebration and family, but the war changed that. Savannah was captured by the British, and the city made plans to take it back. During the breaking of ties with Great Britain, French and Haitian troops used Bonaventure as a landing point. The house became a hospital, treating 200 French soldiers and 12 French officers, after their long journey from Santo Domingo, before the Siege of Savannah (1779) even began. At Spring Hill, the site of the battle, more than 300 soldiers died and another 300 injured were taken to Bonaventure where many others died and were buried in unmarked, unknown graves. From Bonaventure, the troops retreated from the British in defeat. Sadly, after the siege was abandoned, it was noted as being one of the bloodiest battles in the war, and the British remained in control until 1782.

When the Tattnall’s regained the plantation after the war, they became the first family burial in 1802 (Section E, Lot 1), which now includes several generations. The Tattnall’s gave birth to nine children and buried four while residing there. It was a private, family cemetery at the time. In 1803, the original owner, John Mullryne, was buried in the family plot. His wife and six children joined him years later. After the Tattnall parents died, the children moved to London where their grandparents raised them. Two sons later returned to Savannah and inherited the estate but neither lived on the property.

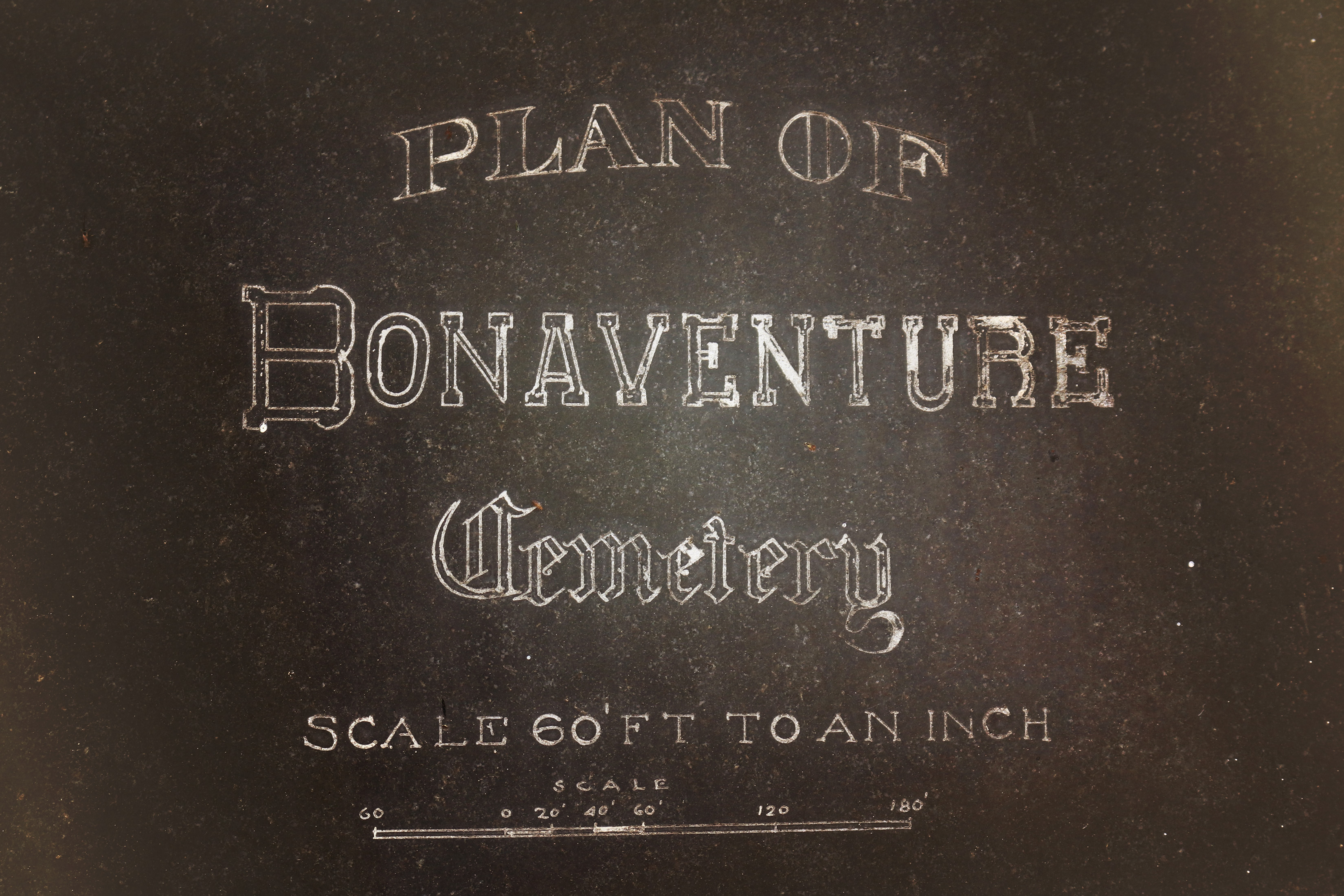

Peter Wiltberger purchased the property from Josiah Tattnall III years later, dedicating 70 acres of the original 600 to be used as a privately-owned cemetery, open to public use. This was a response to the overcrowded Colonial Park Cemetery in historic downtown, and it was part of a national rural cemetery movement that gave the nation its first parks. Many remains from other cemeteries were reinterred at Bonaventure. The remains of Noble Jones, founder of Wormsloe Plantation, were moved from Wormsloe’s cemetery to Colonial Park Cemetery and finally, to Bonaventure in 1848. His monument was the first to be installed. Soon after, Peter’s wife died, becoming the first prominent citizen burial that had not been removed from elsewhere, followed by Peter in 1853. Peter’s son formed the Evergreen Cemetery Company of Bonaventure in 1868 and later expanded it to 140 acres. A map was drawn by John Postell in 1869, which remained mostly unchanged until the city bought the property. One of the names that draws the most attention in Bonaventure, Gracie Watson (1883-1889), was buried during the Evergreen tenure. Other famous names buried during these early years include Mary Telfair, John Stoddard and Alexander Lawton.

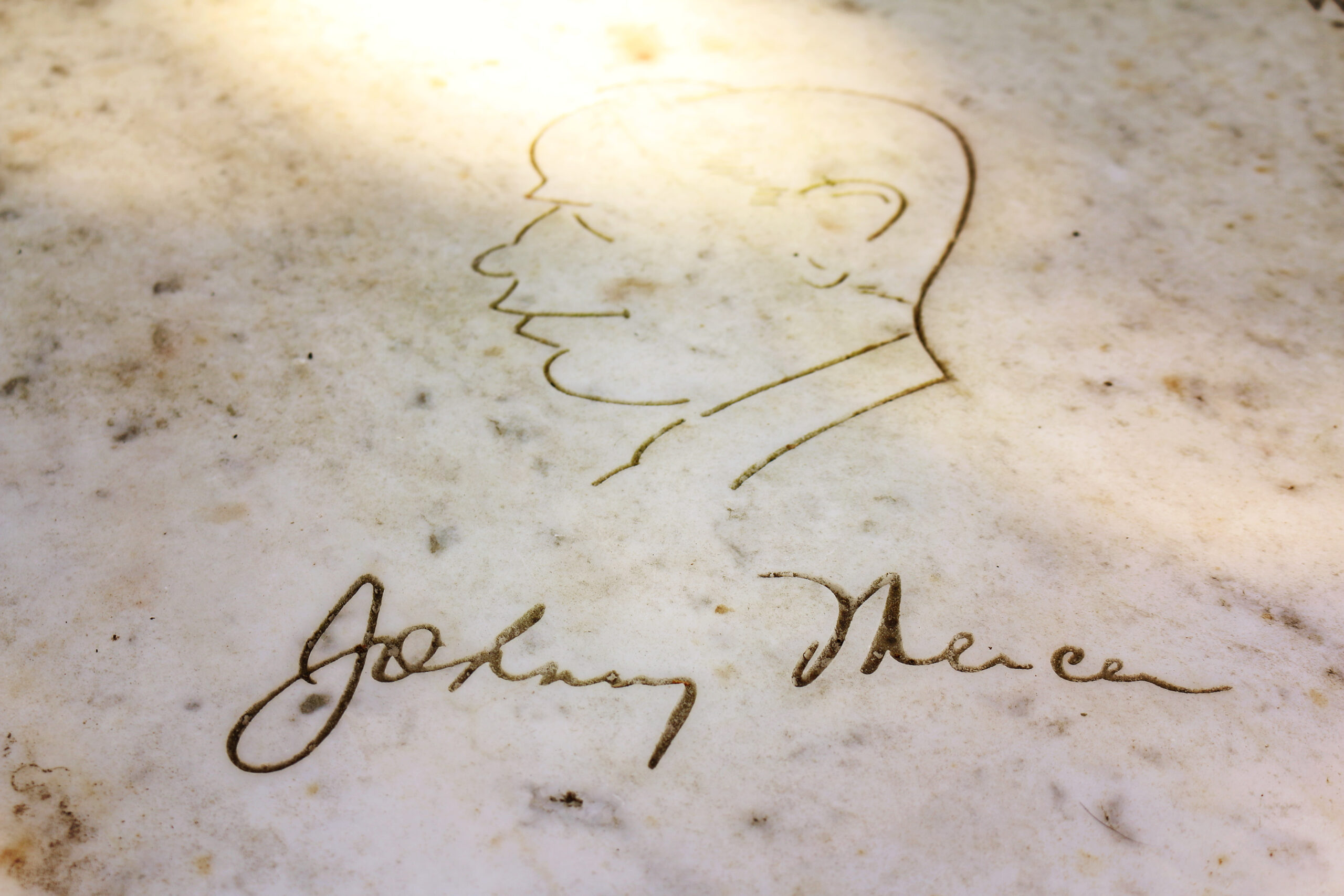

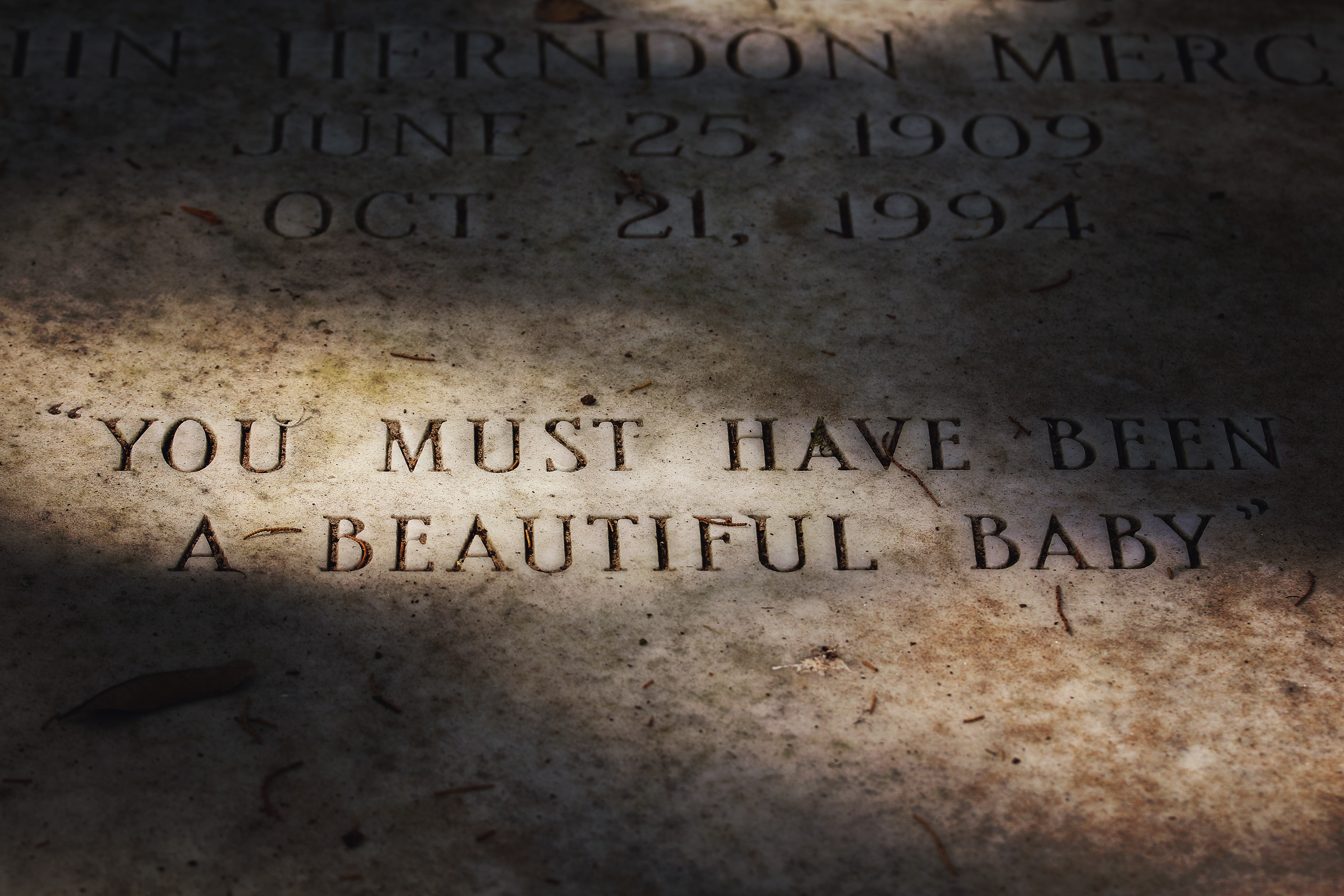

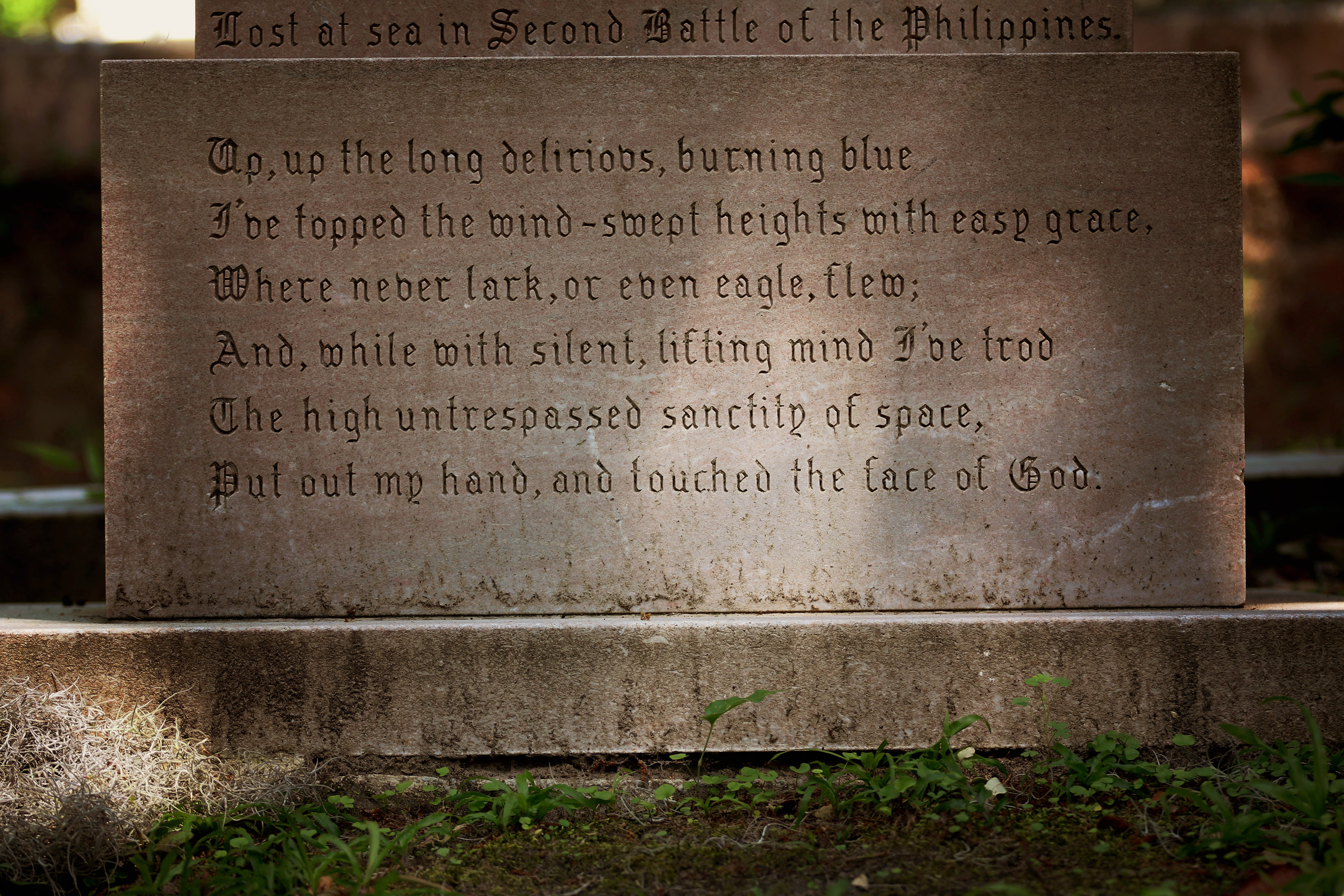

When the City of Savannah took over in 1907, Bonaventure Cemetery grew to 160 acres and saw the addition of a Jewish section, Jewish Chapel and Jewish entrance. Other notable burials, such as Conrad Aiken and Johnny Mercer, happened during this time. Bonaventure is now the permanent residence of actors, authors, songwriters, poets, photographers, entertainers, politicians, historians, soldiers and the great sculptor, John Walz, mentioned earlier. Photographs of the old plantation home do not exist, but it is believed to have stood at Section F, circular in plan and the axis of the cemetery. This became the central axis because the cemetery’s design began with the ruins of the Tattnall family mansion. The caretaker’s house at the front entrance was built prior to the 1900s and is used as offices and a Visitor’s Center today, greeting close to 1 million visitors, annually. Many tourists are now drawn to Bonaventure Cemetery through the non-fiction book Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, by John Berendt, known for the iconic Bird Girl statue photograph, by Jack Leigh, on the cover. It was published in 1994 and became a New York Time’s Best-Seller for 216 weeks. The 1997 film adaptation by Client Eastwood further popularized the story and cemetery. The Bird Girl now exists at the Telfair Academy.

If you are interested in touring with someone who can guide you to the eternal resting places of beloved Savannah residents, beautifully paint a picture of their lives and legacies, expand on the heavy symbolism carved into monuments throughout the cemetery and provide insights on the greater meaning and significance of a vast range of topics, know that Savannah is home to one of The South’s greatest storytellers: Shannon Scott. Beyond his brilliant and charismatic showmanship, his poetic mind is a deep well of knowledge, overflowing from 30 years of life, heart and energy, which he has generously poured into the spirit of Savannah. He has formed relationships and connections with the most captivating and eccentric souls the city has known, which he selflessly dedicates his life to understanding and honoring. Thus, his art form is deeply personal and filled with great love, bringing people and stories back to life in ways no one else can. This translates in the work of his guides, so you’ll be in good hands whether Shannon is on tour or not, but if you’re willing and able, Shannon’s private tours offer a chance to meet and get to know a treasured Savannah character that happens to be the sole, living book of its kind on the city and its past. Shannon is a voice you need to hear.

VOICES FOR THE TREES…

“The trees have been the topic of conversation, legend, news articles, literature, poetry, prose, folklore, paintings, stereo views, photo gravures, post cards, photographs, reports, meetings, brochures and other paraphernalia, frequently throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The trees survived two local wars and five major hurricanes, not to mention lesser hurricanes and tropical storms, too numerous to count. Approximately one-third of the original trees remain.”

– Georgia Urban Forest Council

“The Tattnall graveyard is but a few rods from the garden. The wall around it is entire and the names of the silent inhabitants are engraved on slabs of marble surrounded with trees. But nothing struck me more strongly than the venerable old trees which everywhere adorn this desolate spot. They are covered with a species of moss, a light brown color which hangs about a yard from the branches. It waves with every breeze and reminded me of the gray hair of nature. We approached the place by an avenue of live oaks whose branches formed a complete arch where the roof waved in solemn grandeur.”

– Mary Telfair (buried in Bonaventure Cemetery), 1828

A poem written during Josiah Tattnall III’s ownership of Bonaventure:

“Sublimely beautiful the scene!

And as I gaze around

I feel that nature hath proclaimed

Its consecrated ground.

No rite of man, hath allowed it

But Time – who summons all

To wear the emblems of his power

And answer at his call.

These noble Oaks whose hundred arms

Are stretching wide and high;

(As if the very trees aspired

to reach the glorious sky;)

Even these are shrouded with veil

By nature lent to time;

The long grey overhanging moss

Which marks the southern clime;

O’er stately trunk and branch ‘tis threwn—

But still the bright green leaves,

Like youthful beauty, peeping through,

Seem laughing at the wreaths.

And there the ruined garden walks

Of other days declare,

And the deserted tomb-stone tells

Of valued friends that were.

The world, its follies, and its noise

To solemn thoughts give way—

We feel the power of Nature’s God,

In his sublime array –

Farewell: tho’ other scenes I love,

Where nature’s beauties shine;

The tribute of my heart must be,

Thine, Bonaventure, thine!!”

– M.E.C., 1833 edition of The Georgian

“Bonaventure by Starlight,” The Orion, 1842:

Along a corridor I tread,

High over-arched by ancient trees,

Where, like a tapestry o’erhead,

The gray moss floats upon the breeze; –

A weary breeze, that kissed to-day

Tallulah’s falls of flashing foam,

And sported in Toccoa’s spray,

Brings music from its mountain home.

The clouds are floating o’er the sky,

And cast at times a fitful gloom –

As o’oer our hearts dark memories fly –

Cast deeper shade on Tatnall’s tomb; –

While glimmering onward to the sea,

With scarce a rippling wave at play,

A line of silver through the lea –

The river stretches far away!

And ‘tis the hour when stars above

Reflect the spirit’s inner light,

And the lost Pleiads of my love,

Are kindling in my heart tonight.

I hear a football on the sand,

I feel an arm within my own; –

Full often, in a distant land,

I’ve listened to that trembling tone.

Night darkens into deeper shade,

As on, with solemn pace, we stroll; –

I hear the teachings of the dead,

Like sacred music in my soul; –

So live and act while thou art here,

That when thy course of life is done,

Above the stars thou may’st not fear.

To meet thy father’s face, my son!

– Henry Rootes Jackson (buried in Bonaventure Cemetery)

“Long rows of venerable oaks meet the eye on every side…forming extensive avenues…The hand of man has done this much in planting these living colonnades…richly festooned…with a magnificent drapery of moss which hangs in all possible forms.”

– James Rion, son of Pulaski House hotel employee, hired by Wiltberger to lay out the cemetery, 1849

“Never has a place more beautifully adapted by nature for such an object.” The hanging moss is like “The tattered banners hung from the roofs of Gothic cathedrals as trophies of war in the olden time.”

– Dr. Charles Mackay, Life & Liberty in America, 1859

“This hallowed burial place is like a natural cathedral, whose columns are majestic trees; whose stained-glass is its gorgeous foliage; whose tapestries are draperies of long gray moss; whose pavement is the flowery turf; whose aisles are avenues of softened light and shade; whose monuments are these elaborate and tasteful marble shafts, which tell in simple lines the names of those who here repose in dreamless sleep.”

– unknown early visitor

“Here man can calmly sleep the sleep of death; Fanned by the swaying breezes gentle breath, the dreamless sleep – the sleep eternal, laid Darkly shrouded beneath thy cooling shade.”

– M. Marsh, author, a poem on Bonaventure, 1860

“I went yesterday to see Bonaventure, which is an old Cemetery used by the aristocracy of Savannah. It is one of the most picturesque, as well as gloomy places I was ever in! I wish I could describe it to you. It is planted with live oak and cedar, so thick that they make very dense shade. The trees are large and tall, and have very long branching boughs, which are hung thick with moss. I never saw it grow so long, or the trees so loaded with it before. This gives a gloomy spectral appearance to the place that seems very appropriate to the last resting place of fallen greatness.”

– Jacob Ritner of the 25th Iowa U.S. Infantry, accompanying U.S. General William Tecumseh Sherman on his march through Georgia, 1864

“The most conspicuous glory of Bonaventure is its noble avenue of live-oaks. They are the most magnificent planted trees I have ever seen, about fifty feet high and perhaps three or four feet in diameter, with broad spreading leafy heads. The main branches reach out horizontally until they come together over the driveway, embowering it throughout its entire length, while each branch is adorned like a garden with ferns, flowers, grasses, and dwarf palmettos. But of all the plants of these curious tree-gardens the most striking and characteristic is the so-called Long Moss (Tillandsia usneoides). It drapes all the branches from top to bottom, hanging in long silvery-gray skeins, reaching a length of not less than eight or ten feet, and when slowly waving in the wind they produce a solemn funereal effect singularly impressive. There are also thousands of smaller trees and clustered bushes, covered almost from sight in the glorious brightness of their own light. The place is half surrounded by the salt marshes and islands of the river, their reeds and sedges making a delightful fringe. Many bald eagles roost among the trees along the side of the marsh. Their screams are heard every morning, joined with the noise of crows and the songs of countless warblers, hidden deep in their dwellings of leafy bowers. Large flocks of butterflies, flies, all kinds of happy insects, seem to be in a perfect fever of joy and sportive gladness. The whole place seems like a center of life. The dead do not reign there alone.”

– John Muir, “Camping Among the Tombs,” 1867

“All the avenue where I walked was in shadow, but an exposed tombstone frequently shone out in startling whiteness on either hand, and thickets of sparkleberry bushes gleamed like heaps of crystals. Not a breath of air moved the gray moss, and the great black arms of the trees met overhead and covered the avenue. But the canopy was fissured by many a netted seam and leafy-edged opening, through which the moonlight sifted in auroral rays, broidering the blackness in silvery light. Though tired, I sauntered a while enchanted, then lay down under one of the great oaks.”

– John Muir, “Camping Among the Tombs,” 1867

“[This picturesque place, Bonaventure] is one of the loveliest spots in the world, possessing peculiar charms which have no rival in natural beauty and magnificence.”

– Beale H. Richardson, 1875

“Bonaventure today, after nearly two centuries, is more beautiful than ever for the oaks have grown until they overlap, forming cloistered aisles resembling a great outdoor Cathedral veiled with curtains of Tillandsia (Spanish moss) gently swaying in the breeze, creating an atmosphere of natural mourning.”

– Eva J. Barrington, The Savannah Morning News, 1950